-

The Flawed Frolic of the Ferrari GTO

The Flawed Frolic of the Ferrari GTOTouring in a race car is not grand, even if it is the model’s 25th anniversary

Autoweek (Cover Story)

It had all the right ingredients, except one. As the 25th birthday of the Ferrari GTO (1962-64) approached, covers came off 24 of the remaining 32 GTO specimens. Insurance reps were telexed, car polish flowed, and exhaust pipes coughed out dust. Meanwhile, men inveigled their wives, mistresses, sons or “others” to accompany them on a chateau-to-chateau rally through France. “It will be wonderful, dear,” I could almost hear them say. “We’ll stop for lunch at a three-star and then head on to Baron de Winebarrels place in the evening … ” It would be the luxury rally of a lifetime, again, (they did it for the car’s 20th) and what could be more amusing?

Or so they thought.

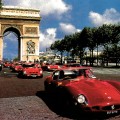

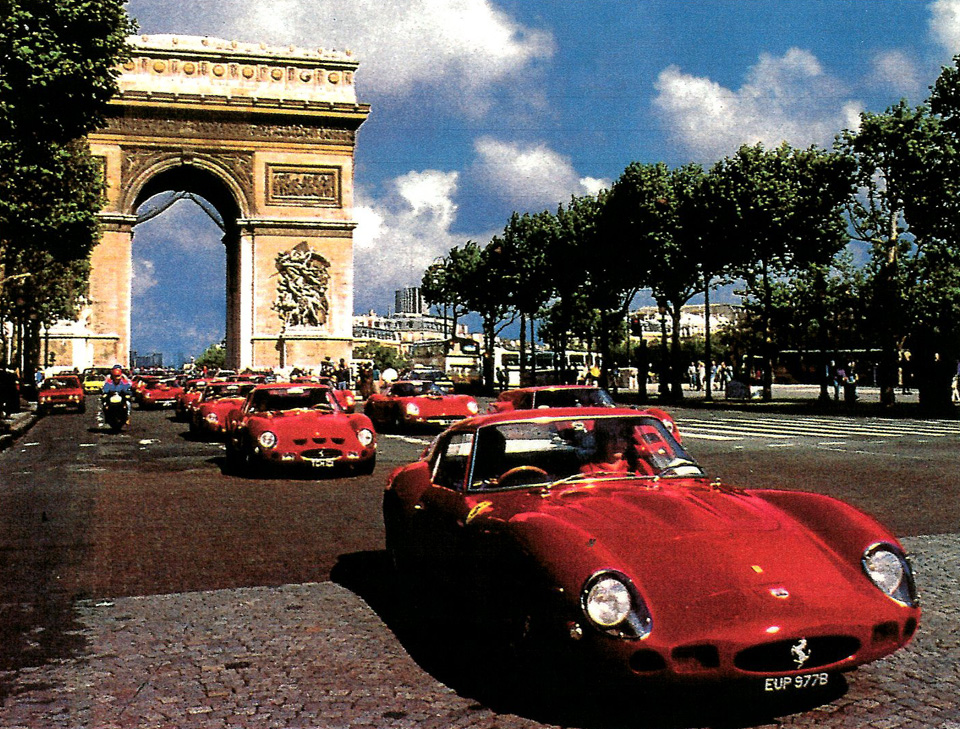

In a triumphal procession past the Arc de Triomphe, the Ferrari GTOs celebrating the model's 25th anniversary parade through Paris.

The overpowering allure of the Midi en été, the thought of showing off some of the world’s rarest, most striking cars was too much to resist, Some of the owners, though, must have had subliminal second thoughts — they must have if they’d ever driven their cars more than a mile or two. Despite its reputation, charisma and cost, the GTO was never anything but a race car.

Even the most painstakingly-restored version is not suitable for extended driving on public roads.

THE CAR

Built for only three years in numbers dictated by orders for racing cars, the 250 GTO has become perhaps the most coveted Ferrari of all — and for reasons that are founded in both its performance and aesthetics. The last front-engined Ferrari to be successful in major racing combines sinuous, feminine body styling — built by Scaglietti and designed jointly by that firm and Ferrari — with some of the most agressively masculine engineering ever presented in a road/racing car. Powered by a 295 hp V12, the lithe yet brutish GTO is, today, the capstone of collections. This car looks fast, from the drooping, vented nose to the ducktail spoiler on the rear deck. For racing, it was wonderful. For collecting, it is critical. But for driving, as we shall see, the GTO is flawed.

THE EXCUSE

Organized by Moet et Chandon (Champagne) and Chateau Mouton Rothschild (wine), the rally was held ostensibly to celebrate the GTO’s silver anniversary, specifically, and l’art de vivre, generally. The latter, now enjoying a revival in Socialist France, means the art of not roughing it. Several months ago, GTO owners were invited to ship their cars and themselves to France this June for seven days of living it up. Lodging in private chateaus was to be provided by friends of the organizers, except for two nights in the Relais & Chateaux hotels.

The only requirements were a GTO, a guest, a passport and a sporting attitude. Not coincidentally, Count Fredric Chandon has a passion for cars; his stable includes a pair of Ferraris, three Bugattis, a Packard and several Rolls-Royces. Baron Philippe de Rothschild, now 86 years old and a proprietor of Chateau Mouton, was a racing driver in the ’20s and early ’30s for Bugatti. A model of the blue car he drove stands in an illuminated glass case beside prized works of art in the drawing room of his Chateau. “Birthdays are meant to be celebrated with Champagne and wine,” piped the Moet representative, rubbing it in, “and Pierre Bardinon , who helped us organize the event, wanted to make sure to have un décor equal to the field of cars.” The phrase “world class” never came up; it was taken for granted.

THE GUEST LIST

It was an eclectic bunch. Some of the guests, one suspected, were distinguished solely by their sound investments; others had reputations that exceeded their cars. Enzo Ferrari sent a note to the effect that “I’m too old to come to Champange to celebrate the birthday of a car I loved very much …. ” and sent Marco Piccinini, director of the Formula One Scuderia Ferrari, to the kickoff in Epernay. Michel Seydoux, president of Gamont, and Jean Boileau, president of Peugeot, both attended the dinner, as did former Ferrari drivers Patrick Tambay and Jacky Ickx. The glitter and glamor made the tour participants certain that they had arrived, but their somewhat hesitant glances at the cramped confines of their cockpits showed hesitancy about the next stage of the gala — going somewhere.

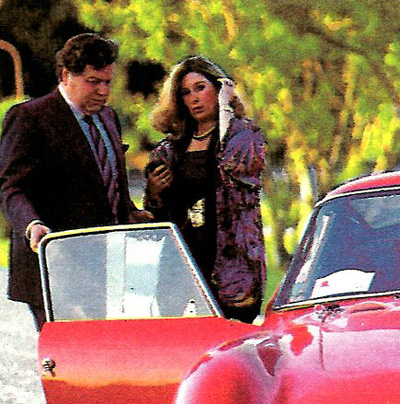

Exiting a race car without wrinkling one's finery was hard.

On the actual rally, there seemed to be two of everything, making the event a kind of Noah’s Ark complete with rainstorms. The two former professional drivers among the GTO owners were Jean Guichet and Innes Ireland. From Wall Street came Peter Sachs of Goldman, Sachs; and Robert Rubin, a director of Drexel, Burnham, Lambert. There were two Ford concessionaires from England, as well as two British celebrities: actress Jane Seymour and Pink Floyd’s drummer, Nick Mason. Investors and industrialists were also present, along with a solitary dentist from Minneapolis. The nationalities included French, English, German, Italian and American.

Five Ferrari technicians were stationed as watchmen at checkpoints throughout each day’s journey. The various suitcases, crammed with leftover work, dinner jackets, bow ties, curlers, jewelry, and bottles of wine, were stashed in a van that preceded guests to their evening stops by virtue of a faster, less scenic route. Journalists and photographers were not present on the actual drives, as this was meant to be a treat for GTO owners, not admirers. Also, some of the Europeans in the group (the head of a reknowned Italian mineral water company, for example) deliberately avoid publicity. Fears of kidnapping and terrorism weigh heavily these days, not to mention theft; a GTO sold a few weeks ago for one-half million dollars.

THE JOURNEY

And they’re off! On Monday, June 8, the entourage left Paris for Reims and an outing at the track where GTOs won races in 1962, ’63 and ’64. Lunch at I’Abbaye d’Hautvillers where Dom Perignon, the Benedictine monk, once lived was followed by a sumptuous dinner served in the cellars of Moet et Chandon.

Tuesday found the group near Tours, billeted in the Chateau d’Artigny.

The next day was no less grandiose in planning, but by then the reality of driving 25-year-old race cars for extended stretches had eroded the veneer of sumptuousness. Even the world’s best wine cannot disguise the reek of petrol fumes or condition the air of a tightly-enclosed cockpit. Lunch at distillery Du Peu (owned by Cognac Hennessy) did ameliorate the aches somewhat, but by the time dinner at Chateau Mouton Rothschild arrived, the guests were somewhat sore.

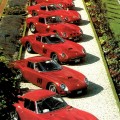

Thursday and Friday followed apace, with wonderful lunches, fantastique dinners, and berths in the world’s best beds. The last day culminated in la Creuse, where the Bardinons, owners of Le Mas du Clos, boasted stables of race horses and thirty-five Ferraris, including three GTOs.

A TYPICAL EVENING, MIDWAY

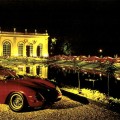

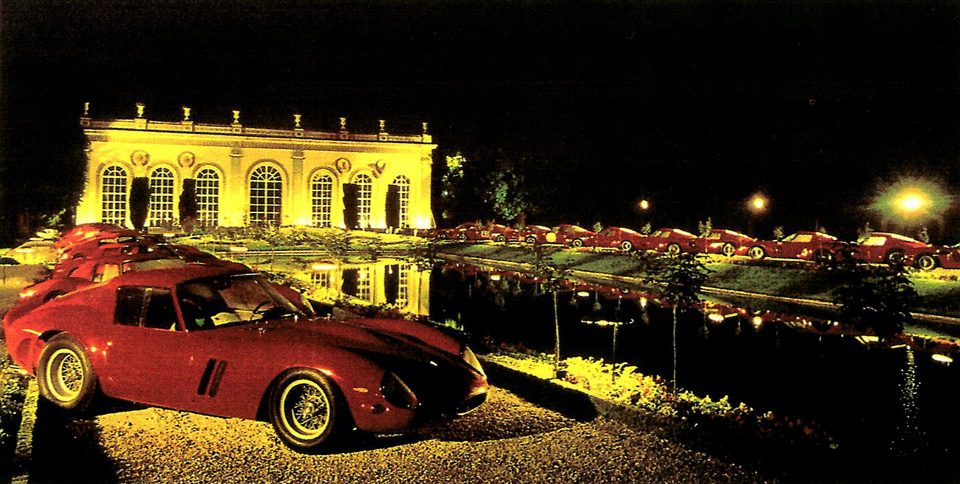

The proud owner of a glistening GTO slammed the car into reverse using two hands. Grunting, he engaged the shifter and the car lurched backward into position. The owner, a tall Englishman, emerged from the vehicle in stages, his cheeks the color of the car’s hood. It was a moment for the Marx Brothers. “Well it’s not a true bloody perambulator, you know!” he bellowed. Some photographers had tried to coax him into parking so that they’d catch the last rays of the dying Bordeaux sun with Chateau Mouton in the background; Mouton was the host for that evening’s dinner. Slowly, the balance of the $35 million worth of hardware came through the gates, past the sphinxes, and the occupants creakily emerged. One gentleman popped open the hood of his GTO and delicately spread a blanket over the engine, as if it were capable of catching a cold. Others merely straightened their ties and put on their jackets as the ladies adjusted skirts and slathered on perfume, trying to overpower the oil and gas odors which infiltrate a GTO cockpit. Next, they all put on smiles to greet people they hadn’t seen in more than two hours. GTO owners are clubby; despite differences in background, they get along. After some milling around, someone decided that the cars should be moved to Baron Philippe’s estate, where they could be given a safer berth than the one provided by Relais de Margaux, that evening’s digs. The cars were driven in caravan to a quaint courtyard formed by the stables and parked meticulously. GTO owners understand how to position their cars photogenically they’re collectors and have done it countless times. Security guards with dogs patrolled the area until morning.

“We don’t really know what. she’s doing here or who brought her,” said one of a trio of middle-aged English ladies during cocktails. “They were filming her when we started out, though I don’t know what for,” remarked another. “I suppose we don’t shine enough,” commented the third, with dead accuracy. Jane Seymour had been imported for four days by Moet to add a special “je ne sais quoi” that was lacking: glamour. According to Jean Berchon, Moet representative, “We wanted a godmother for the rally and Jane happens to love champange and fine cars.” Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous descended on Epernay at the same time, hence the camera crew. It was the most blatant act of PR in an otherwise non-voyeuristic week; many of the guests, however, were oblivious. They were more concerned with wine and each other’s chassis numbers than with girls or cameras.

At times the romance and glamour lived up to its advanced billing.

Just before dinner, I had been told by Dominique Pascal, a French auto journalist and Ferrari expert, that the last GTO at auction went for an astounding price. Curious, I asked around and determined that some people had owned their cars for 20 years, others for barely two. Had the emphasis shifted from mere enthusiasts buying the cars to professional investors making the purchases? An English collector of airplanes and cars who was seated on the opposite side of the table “immediately denounced me as a vulgar, money-conscious American: “How can you sit there and suggest that any one here could define his car as having value in terms of money?” he asked. He added that he purchased his model 17 years ago. Nick Mason, who had bought his GTO many years ago, felt that the prices were artificially inflated and that he would not have considered buying one today. “It’s not worth it,” he said, “because they’ve been altered. Unlike a painting, the cars can be heavily retouched to the point that all you’re buying is a chassis number-plate.” Mason pointed out that the GTO is one of the few collectibles in which resemblance to original condition isn’t a primary factor in the object’s value. Its rarity seems to take precedence over its aesthetic value and sometimes crosses the line where it can no longer be appreciated sufficiently as art, but only as a machine. Indeed, the variances in the detailing and restoration of the 24 GTOs were considerable. The least authentic was the well-chronicled GTO “squareback” van conversion. The most factory-like were the GTOs belonging to collector Pierre Bardinon, for whom authenticity is a fetish.

Ironically, Bardinon is not a full-fledged purist: He corrupts his cars by emblazoning them on the front fender with a small diecast seal bearing the name and likeness of his estate.

The wine, Chateau Mouton 1971 and Champagne flowed in abundance and kept conversation bubbling. The meal itself consisted of a cold buffet that included some flavorful regional dishes. Evidentally , Baroness Phillipine de Rothschild. the Baron’s only child and technically our hostess ill absentia, doesn’t like to serve à table, guests with whose tastes she is unfamiliar, hence the buffet.

As a result, it was a meal for strangers, albeit impeccably attended by an elegant and youthful staff.

THE DENOUEMENT

The fact that some of the rally-goers were bored with each other by the third dinner party was an important, but not crucial, factor as to why this particular rally could never really succeed. Neither was the intermittent rain, although it certainly didn’t help. Surely, to drive from chateau to great chateau and sleep in them must be fascinating. And all those meals! Those exquisite wines!

But think about the gormandizing in combination with the transport: the Ferrari GTO. It was built as a limited-edition racing car, not as a luxury tourer. It was designed to win LeMans in twenty-four hours, not the heart of France in seven days. What an effort to repack, drive all morning watching out for road markers that aren’t there, behind immobile trucks and 2CVs, and then to load up on irresistible viandes et vins, followed by a crawl back into the car and a hustle to the next chateau. Suddenly, it’s six o’clock and time to unpack, shower and change for dinner … for six nights and seven days. Don’t forget that this is France, and your car isn’t properly insured. (In fact one of the GTOs flown to Frankfurt had been misplaced for two days. Its owner was given a container with someone’s red Daytona, instead.) All this in the tiny interior of an automobile that was intended, from the beginning, to be crude; even the windows only open halfway, like sliding doors.

An exotic car dealer from Texas who was a passenger in one of the GTOs put the holiday into perspective: “I felt this dripping on my shoulders coming from behind, as if oil mixed with rain was splashing up from the road. You have to remember that the car holds about twenty-five gallons of oil and the filler tube crosses right behind the passenger seat. Also, GTOs were constructed in a series of layers,” he added, “sometimes leaving slight apertures between the layers so that wind, oil, water and noise can find their way through.”

The cars were in varying states of repair, and though they all looked wonderful, they blithely took their toll on occupants in different degrees. Whether it was due to that drop of oil on a new pale-blue Polo shirt, or the faint smell of gas working against a fresh splash of Chanel No.5, or even that slight backache in the lumbar region — the GTOers learned one thing, indelibly: you may leave a Ferarri GTO, but it will never leave you. MG