-

Bob Weir

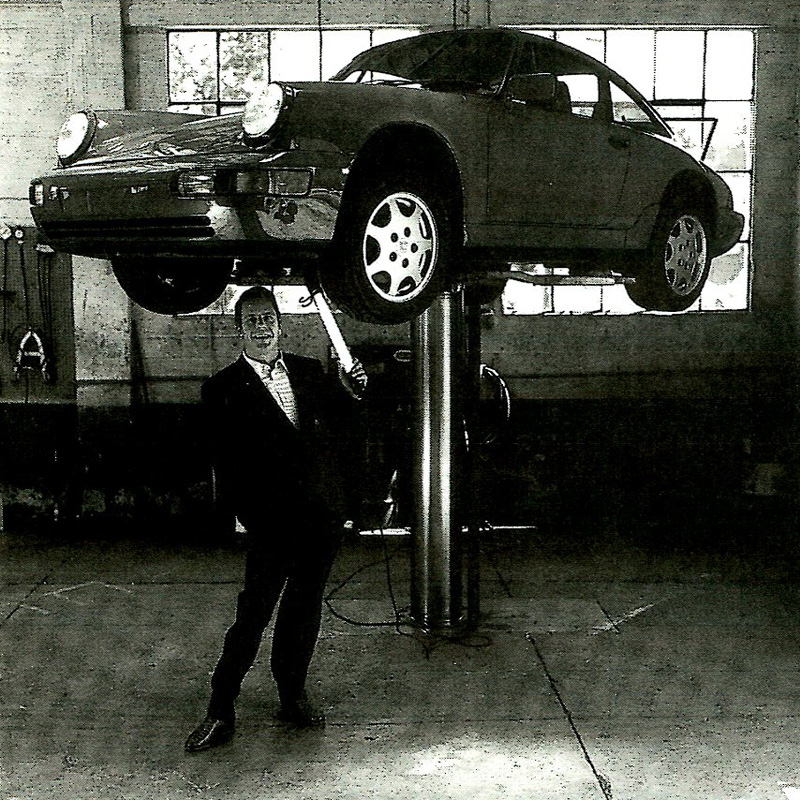

Bob WeirA bisexual Porsche: The Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir gets down in the new Carrera 2 with a Tiptronic Dual Function transmission

Vanity Fair

For about as long as the Grateful Dead has been the top cult rock band, the Porsche 911 has been the great cult sports car. The immediate precursor to today’s 911 was a version of the car James Dean crashed and killed himself in during the mid-fifties. There has traditionally been no area of compromise with either the car or the band, but recently both had to come to grips with the same marketing predicament: how to reach out to a wider audience without abandoning the hard core of loyal followers. Their solutions were similar. The Dead repositioned themselves by going into the studio and recording a rather generic album of pop tunes that led to increased radio airplay. At live concerts, which are now in stadiums and large arenas, they revert to their distinctive rambling, improvised sound. The tinkering the Germans did with their classic was more subtle. In 1989, Porsche, the last great sports-car company to remain in private hands, smoothed out the rough edges of the 911 and sent over a new fourwheel-drive, five-speed model, the Carrera 4. This year its two-wheel-drive sibling, the Carrera 2, arrived here bearing a “Tiptronic Dual Function” transmission, i.e., an automatic that can be switched into a manual mode. An automatic 911 is news, because ostensibly no Porsche enthusiast would ever want one, although the Carrera 2’s automatic is brilliantly engineered. The car is supposed to appeal to American couples, since many women here, presumably, don’t like stick shifts. The Tiptronic is something for everybody. (A fully manual Carrera 2 is also available.)

"It's the kind of car that lures you into sporty driving," Weir said after spending time with the Carrera 2 Tiptronic.

The car we lent to Grateful Dead guitarist and singer Bob Weir was a bright-red 911 Carrera 2 Tiptronic. Weir owns a BMW 535i sedan, and he was drawn to the flashy little Porsche, which offered him a very different driving experience. “I had some dangerous fun in this car,” he reported. “The ballyhoo about its handling is probably well deserved. It’s a demanding automobile.” We were motoring along a road of threaded switchbacks up to Weir’s house, which juts out from the wooded mountainside near Mill Valley, a formerly bohemian and now affluent enclave outside of San Francisco where he has lived for twenty years. The road became steeper and steeper, and Weir, whose BMW is a stick, was still feeling a little uncomfortable with the Tiptronic. “Anyplace where there’s traffic congestion, this transmission makes sense, but it’s not like a manual transmission. It doesn’t shift when you want to shift, it shifts when it wants to shift. And it can take a moment or two-see?” Weir was operating the car in the “manual” mode. The gearshift lever mounted on the floor console between the front seats has two gates: the traditional slot is augmented by a parallel track that the driver can slide the lever over to. The second track is for manual shifting, without a clutch. One simply tips the gearshift forward to move to a higher gear, and backward to shift to a lower gear.

It sounds contrived, but the Tiptronic system really does have many of the attributes of a manual transmission, particularly once you get used to the absence of a clutch. It’s not just a pretentious version of existing three- or four-speed automatics. Porsches are designed to be driven fast, at the peak ranges of their performance curves; under these circumstances it would be far too easy to damage the engine of a traditional automatic by holding it in second gear when the number of revolutions per minute demands that it be placed in third. Also, with conventional automatics, one can easily slide into the wrong gear by applying too much pressure to the lever. With the Tiptronic, you can’t blowout the engine, because it won’t let you: a microcomputer delays your ill-timed shift until the engine speed is suitable. The joy of driving the Carrera 2 is in watching the tachometer (an enormous dial directly in the driver’s line of vision), listening to the speed of the engine, and finding the precise moment when it’s appropriate to shift, before the computer does it for you. But after spending several days with the car, Weir had reservations. “To have to run it through all sorts of computer circuitry to prevent the driver from blowing up the engine is an inherently flawed situation,” he decided. “That little hesitation between the time you tell it to shift and when it shifts takes getting used to. You learn to work with it, I suppose, and if I were living in L.A. this would be a whole lot more attractive to me. If I wanted to take it up to Mulholland Drive and bat it around, I’d put it in the Tiptronic slot.” (The “hesitation” Weir was talking about was hard for me to detect, but if it existed it might have been a consequence of the workout the Road & Track editors gave the car right before Weir drove it.)

Weir pulled up to his mailbox on the roadside. “You want to drive this car very smoothly. If you do that, and just sort of caress it through the corners and other maneuvers, it responds beautifully. It rides like a buckboard, however, as you see.” The pavement of the narrow road was patched and broken in places, and the 911’s suspension, tuned for the autobahn, fought it. “The ride is very, very stiff,” Weir said. “No one who would buy a Porsche would have it any other way. That’s what Porsches are about.”

Up at the house, Weir showed me his black Corvette convertible. “This is a 1963, the first year for the Sting Ray. The engine and running gear are better than new.” (The body, however, wasn’t restored. Northern California chic, I suppose.) “It’s got the old Rochester fuel injection. I bought it for 3,200 bucks in 1976. It’s the old American fun machine. This car is more fun to drive legally than just about any car on the road. That’s another point about the 911,” he said as the Vette’s hood came down with a thud. “I’m kinda surprised that they don’t have roughly the equivalent of handgun laws, pending legislation, regarding these kinds of cars because basically the 911 is nice in the corners around town, but it doesn’t really do what it does until you’re breaking the law. Past a certain speed in California, and I’m not sure if it’s 85 or 100 m.p.h., it’s a felony.” (Actually a $500 fine and the possibility of losing your license.)

A screenwriter (The Color Purple) friend of Weir’s, Menno Meyjes, had driven down to L.A. with him in the 911. Meyjes has been to the Bondurant performance-driving school, and has a long-standing interest in Porsches. They drove the car over mountainous Highway 33, from Ojai across to Route 5. Previous 911s were known for having their rear ends break loose during hard cornering, sending the car into a spin. In the Carrera 2, much of that slippery handling has been eliminated; in the Carrera 4, it has been eliminated entirely, which is why it’s a safer car. “With the Carrera 2, you definitely have to set up your turns correctly — you cannot make corrections after you tum into the curve,” Meyjes told me. “I wouldn’t recommend it to people who are going to be on the phone a lot when they’re driving. This is an adult-size Porsche that can also get you into real adult trouble — quickly. But,” he added, “I think that’s ultimately a good thing, because it requires you to concentrate while driving if you’re going to push it at all. It’s not forgiving. It forces you to sharpen your driving skills and not be lazy. That’s good; it’s very honest.” Weir concurred: “It’s the kind of car that lures you into sporty driving, and then you’re driving for fun rather than transportation. At some point or other you’re going to be put to a test with it.”

“If one is buying a Porsche, one is well advised to special-order it,” Weir remarked. “They don’t pay a lot of attention to creature comforts. I would probably install a pair of Recaro seats, because the standard ones don’t have the amount of lumbar support that I like.” (They fit me perfectly, but at six feet, Weir’s two inches taller.) “And I would tell them to forget the stereo — I’ll do it. They’re making an enthusiast’s car, no bones about it, but I personally don’t think it has to have all the luxury of a go-cart. The seats — I don’t know if they’re real leather or not, do you?” The black 911 seats looked vinyl-covered, and the sound system was fairly lousy. “And before I forget,” Weir said insistently, “the windshield wipers … I had an opportunity to use them last night. It actually sort of misted here and the wipers are a joke. They just didn’t take the water off the windshield, even at regular speeds.”

Quibbles aside, the Carrera 2 Tiptronic is tempting. “The car almost converted me into an enthusiast,” Weir said. “But my driver’s license is a fairly precious item for me. If I had a car like that … It drives so wonderfully at higher speeds that I’m afraid my license would disappear pretty fast. And I don’t like to have to spend all my time looking in the rearview mirror. I don’t like that gnawing fear in the pit of my stomach. I could live without all that stuff,” he said, trying to convince himself.

O.K., so what does Jerry Garcia drive? “He’s got a BMW 750iL,” Weir said, referring to the $72,000 fat eat’s twelve-cylinder executive sedan. “It’s a big rocket ship.” MG

published September 1990, photography by Ken Probst