-

Mr. Bhogilal’s Used Car Lot

Mr. Bhogilal’s Used Car LotThe elusive Bombay industrialist owns 200 vintage and classic cars. He uses them all, too.

Town & Country

“The Queen’s Necklace” is the nickname given to the nighttime view of Bombay’s great ocean boulevard, Marine Drive, as seen from the elegant neighborhood of Malabar Hill. Under the harsh Indian sun, however, the necklace has little glitter-Bombay’s decay is pervasive-unless Pranlal Bhogilal is on the move. A quirky 55-year-old multimillionaire industrialist, Bhogilal dazzles as he rolls down Marine Drive in a spotless Rolls-Royce, a Packard, or some other vintage car, gliding serenely through a sea of Morris Oxfords and Fiats made in India. If the day is bright, the motorcar might be a drophead (convertible), affording gawkers a full view of the chauffeur in white livery and his passenger in an impeccably tailored, cream-colored safari suit with uncut-ruby buttons. Bhogilal likes epic grandeur; if the ceaselessly buzzing movie factories of Bombay were ever to make a film version of his life story, it would undoubtedly be called The Last Maharaja.

Bhogilal’s tastes are certainly royal, and he indulges them with a majestic eccentricity. He owns and maintains at least three palatial estates, teeming with hundreds of servants, and has some 200 vintage cars. Exactly where he got the money to support such a lifestyle is a little mysterious. Friends say he made most of it himself, but Bhogilal implies that the roots of his family tree extend indefinitely back in time in Ahmedabad, the country’s most prosperous city, located in the state of Gujurat in south central India. He proudly displays a family crest (a crowned pair of wooden sandals flanked by a prancing horse and a lion) in every possible place-from letterheads to gates to car doors. He cites a speech, made by a finance minister, pinpointing his father as “the eleventh richest man in prepartition India, the Nizam and Barodas included.”

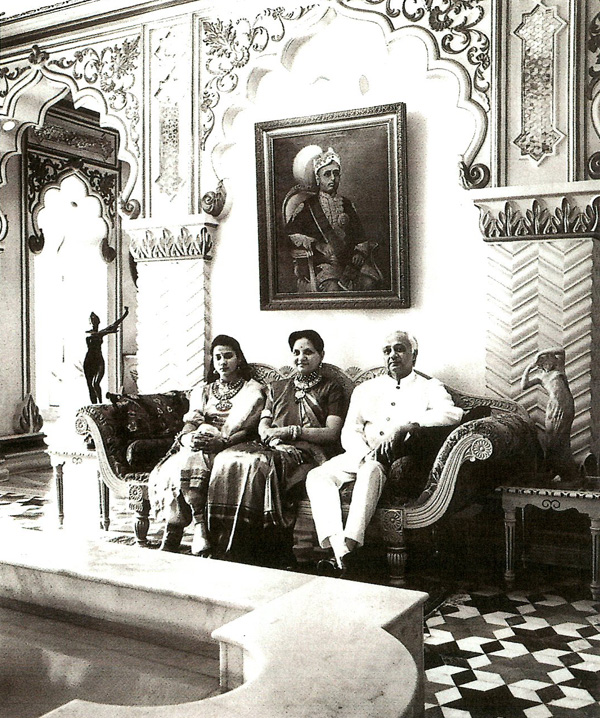

Pranlal Bhogilal, above with his wife, Bharati, and daughter, Chamundeshwari, in his Bombay home.

When asked directly about the roots of the family fortune, however, he gives an elliptic reply: “Well, if you take into account the fact that industrialization is roughly 100 years old, and that the family history has to go far beyond it to several hundred years, then it has to be something beyond industry. In our case, it has been mostly land, import and export trade, and banking.” Many of the original holdings were lost, he smoothly explains, either when the banks were nationalized or when India was partitioned, since the family lands lay mainly in East Bengal (now Bangladesh). According to researchers, these claims are hard to substantiate. Shoba De, an immensely popular novelist who also chronicles Bombay society, puts it waspishly: “Even in business circles of Ahmedabad, no one seems to have known his antecedents. It’s a conscious cultivation of a time warp.”

Does it matter? Pranlal Bhogilal today is chairman of the privately held Das Group companies, which include steel, textile, paper, and sugar milts; starch factories and chemical plants; and real estate and plastics companies. He also owns, besides his fleet of motorcars, drawerfuls of colored diamonds; cabinets stocked with imperial Ming plates and jades, museum-quality Chola bronzes, Moghul miniatures, and such objects as a Bernini marble and Czar Nicholas II’s candelabras, acquired from the Nizam of Hyderabad.

Unlike most collectors, he uses his treasures, wearing his precious stones, dining with his silver, and, most unusual, riding in the cars. “Cars are not to be kept as gilded lilies and stored in climate-controlled garages,” he scolds, putting down buffs in the West who rarely drive their vintage cars. His machines stand like cattle in the barns of his various estates, ready to be pushed out at any moment:

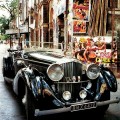

Bhogilal's 1934 3.5-liter Bentley, above in Bombay.

Cadillacs, Daimlers, Packards, Lagondas, Bendeys, Rolls-Royces, Chevrolets, and Buicks. A full-time staff of thirty men looks after the cars, retooling the engines, replacing the upholstery, beating out the dents, and doing whatever else is needed to keep their juices flowing.

On a typical weekday, Bhogilal phones downstairs to his “controller of garages” from his Malabar Hill house (a fortresslike sandstone mansion called Daskot) and tells him the day’s needs. “If I am to be accompanied by one or two other executives, he selects a car that is not a two-seater or a two-door convertible. If he thinks the evening will permit an open drive, then a convertible will be brought out-something from the ’40s, ’50s, sometimes even the ’30s,” says Bhogilal.

Once the conveyance is selected, it is feather-dusted and the engine warmed up. Then the iron gates of Daskot open to allow six men — the gate boy, the flag man, the duster, the mechanic, the driver, the superintendent-to emerge. Traffic snaking down busy Walkeshwar Road is stopped while the glistening, ancient machine chosen for that day turns from Daskot’s courtyard into the mad flow of cars and heads toward Das Chambers, Bhogilal’s downtown offices. If the engine dies close to home, as often happens, a member of the staff will come running to revive it. If the car stops somewhere farther away — oh, well, someone will help push it to a safe spot to await help.

As a major collector of rare automobiles, the tycoon is often asked for favors. His 1934 Buick appeared in the film Gandhi after Bhogilal brought to director Sir Richard Attenborough’s attention the fact that Gandhi simply would not have used a Rolls-Royce or Bentley. “Those were not the cars used by the national leaders who were representing the masses,” he advised. More recently, when asked to loan a Rolls-Royce for a wedding extravaganza, Bhogilal offered the use of his modern Phantom V, once owned by Queen Elizabeth II. It was declined in favor of a vintage model, which quickly boiled over in the horrendous traffic. “And they had done it up with flower decorations,” Bhogilal recalls, smiling at the memory of the stranded beauty.

Many of his cars come with distinguished pedigrees. Besides the queen’s Rolls, he has King George VI’s Daimler and machines custom-built for the maharajas of Baroda, Mysore, and Indore. Others were retrofitted by their aristocratic owners with such items as gun racks for tiger shoots. In the early 1970s, when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imperiously stripped the maharajas of their titles and government stipends — they had already lost their authority to rule — many royals had to open their palaces to tourism and sell off their precious belongings, including their motorcars. “In times gone by, maharajas bought a Rolls-Royce the way you would buy a shirt ‘or trousers,” Bhogilal says. “Years might pass before they would ride in it for the first time. Or somebody might say, ‘I don’t like it,’ and it would be given away or left idle.”

He bought this stately 1947 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith (body by Hooper) from the Maharaja of Mysore.

Bhogilal found his true identity and his niche in Bombay society as the importance of the old royal families gradually diminished. The maharajas had traditionally seemed denizens of a dream world into which the masses hoped to be reincarnated. They were living reminders of the subcontinent’s precolonial greatness. And they could also be relied on for charity. When Indira Gandhi deprived them of their remaining wealth, the vast majority of Indians were deprived of their fantasy models. To replace them, the populace turned to national epics like Mahabarata, to films and television — and to a new kind of maharaja. Pranlal Bhogilal helped fulfill the need for conspicuous success stories; he became a marvelous Hindu hydrangea, thriving on business acumen and royal aspiration.

Consider Dashiana, the lavish estate he maintains in the heart of Ahmedabad. An old palace surrounded by fountains and formal gardens, it is the place where the Bhogilals reportedly welcomed the Aga Khan, the Rothschilds, the von Thurn und Taxises, and Gandhi himself. Like all the industrialist’s residences, it is kept clean and fresh, he says, “as if the staff were expecting us for dinner.” (In fact, most of his houses are seldom used, for he no longer travels with his wife and young daughter, fearing that the family could be wiped out in one stroke. He spends much of his time in Bombay.)

For all the display of wealth, Bhogilal takes great pride in the fact that his father was an ascetic. “He never had more than three suits of clothes at any given point, and he spent nothing on himself, only on charity.” His father saw himself humbly, as a sort of trustee, which explains the honorific title of the family, das, meaning “slave of God.” All the family properties bear this name, from Dashiana to the philanthropic Das Foundation. Like his father, Bhogilal is a devout Hindu and a generous public benefactor. “We have tried to use our wealth and our position to help alleviate human miseries,” he says. “There is really only one religion. Simply stated, it is: Do whatever good you can toward any other soul.”

Another part of his function, this slave of God firmly believes, is to carry on lavish family traditions and keep up his estates. Anything less would mean firing an army of loyal servants who depend on the family for their livelihood. Then, too, Bhogilal feels he must live up to the expectations of the people by being extravagant while he can — Indian fatalism grants him only a moment — and to take obvious pleasure in doing so.

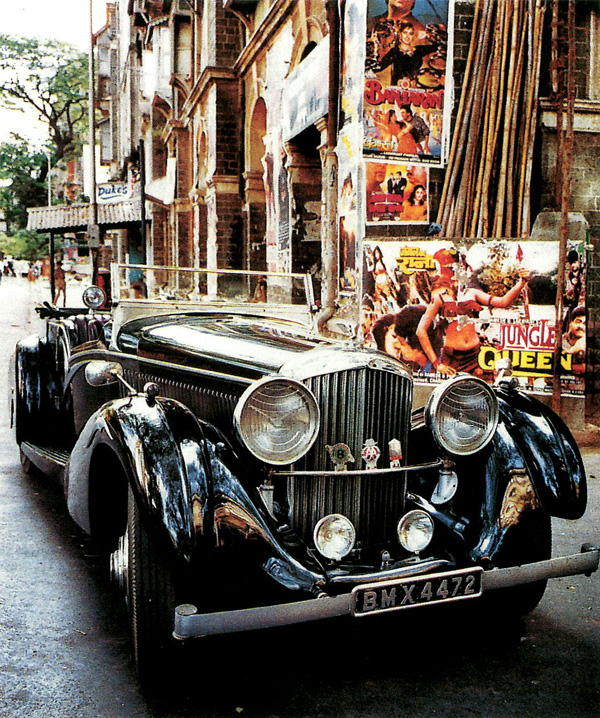

His 1932 Rolls-Royce "duck-tail," custom-designed for the Maharaja of Mandi, steals through a silent town.

The cars fit into his philosophy on several levels. First and foremost, he reveres the great machines as works of art, pure and simple. Second, many have strong personal associations. Some of the automobiles came from his family — Bhogilal says the clan has not sold a car since the early 1900s — and he bought many others when the maharajas first put them on the market. “In the early 1970s, the Indian aristocrats sold off their cars at a pittance,” he says. “They thought an old car was worth nothing, and that it was both desirable and advisable to replace it with something more modern and fashionable. They lacked the foresight and imagination to retain them.”

Because Bhogilal does not sell any of his classic and vintage cars, he clearly does not collect them for investment purposes, although he is the first to concede that they have appreciated tremendously; indeed, many maharajas and maharanis discovered as much after sending their moldering Daimlers and Bentleys to auction houses in London and New York, getting prices that allowed them to buy a pied-a-terre in Mayfair or on Park Avenue. But the true value of the machines, argues this collector, lies in their ability to inform and inspire, for they elegantly convey the history and traditions of the epoch in which they were made. That this era coincides with the heyday of the Raj does not bother him in the least. Bhogilal likes harking back to grander times.

To him, the cars form as priceless a part of India’s heritage as its great bronze and stone sculptures. To retain the machines, the government of India, with the full encouragement of the Vintage and Classic Car Club of India, has placed an embargo on their export. This organization just happens to be run by a man who would stand to reap a fortune if he exported his collection — Pranlal Bhogilal.

Bhogilal feels none of the urge, so pronounced in the West, to return the automobiles to their “original” condition. Quite the contrary: He will gladly change anything he feels can be improved, especially if it keeps the venerable machines on the road, where they can be seen.

So every morning, when the doors of Daskot swing open, Bhogilal is happy to appear, resplendent, in his Lagonda, Hispano-Suiza, or Rolls-Royce. If the muffler roars and bellows, if the engine seizes up, so be it. Let the car grind to a stop and lie immobile in the turmoil of Bombay traffic. Let a murmuring crowd gather around the machine. But, he will say, notice how the gawkers remain benign and orderly, how they seem to be entranced. They need the vision of the beached automobile. For them, it is an existential and uplifting sight. Knowing that, Bhogilal is ready to put up with the inconveniences of being stalled; to him, it’s all part of being a kind of trustee. MG