-

The Bentley Continental GT

The Bentley Continental GTA New Coupe Heralds an Overdue Renaissance for the Legendary Marque

Architectural Digest

“If you go back to the early days, the Bentley was a very simple automobile,” says Dirk van Braeckel, design director of the first genuinely new Bentley in half a century, the Continental GT.

“They raced at Le Mans. It was about the engine and how you experienced the power that it would deliver in its own fashion.”

Under Rolls-Royce ownership, Bentley became the slightly lower-cost alternative to the flagship Rolls, its legacy of endurance and speed blurred by bodywork created for the Flying Lady, not the Flying B. In 1998 the brands separated, and BMW purchased the Rolls-Royce name, its logos and its iconic, instantly identifiable radiator shell. Volkswagen bought the Bentley trademarks, as well as the historic Rolls-Royce factory in Crewe, England. Volkswagen AG has always been passionate about motor sports, particularly through its VW and Audi divisions; it also owns Lamborghini and Bugatti, two companies that are synonymous with luxurious, ultrahigh-performance cars. This passion is essential in understanding the very complex, idiosyncratic and thoroughly fascinating Continental GT.

The Continental GT is Bentley's debut under its new ownership by Volkswagen. It was designed and produced at the recently refurbished Bentley factory in Crewe, England.

“W 0. Bentley’s dream as a little boy was to create a road train, something low-revving that drove like a locomotive, with a big engine, lots of power, lots of torque, which was the key to success at Le Mans in those days,” van Braeckel says. “The Bentley engines were never stressed. So with the GT, we built the car up from the engine.” The bodywork of the GT is an organic three-box enclosure made up of the massive engine, a generous seating compartment and an ample trunk. “We work with engineers on setting the basics, which have an impact on the style of the car,” he says. Most manufacturers keep designers and engineers separate.

The Continental GT is critical to the reintroduction of Bentley as a stand-alone luxury brand. While the core value of performance is still there, the GT evokes none of the simplicity of the very early Bentleys and little of the fussiness of the Rolls-era cars. It is, perhaps, the Bentley that might have been, had W.O. never lost control of the company.

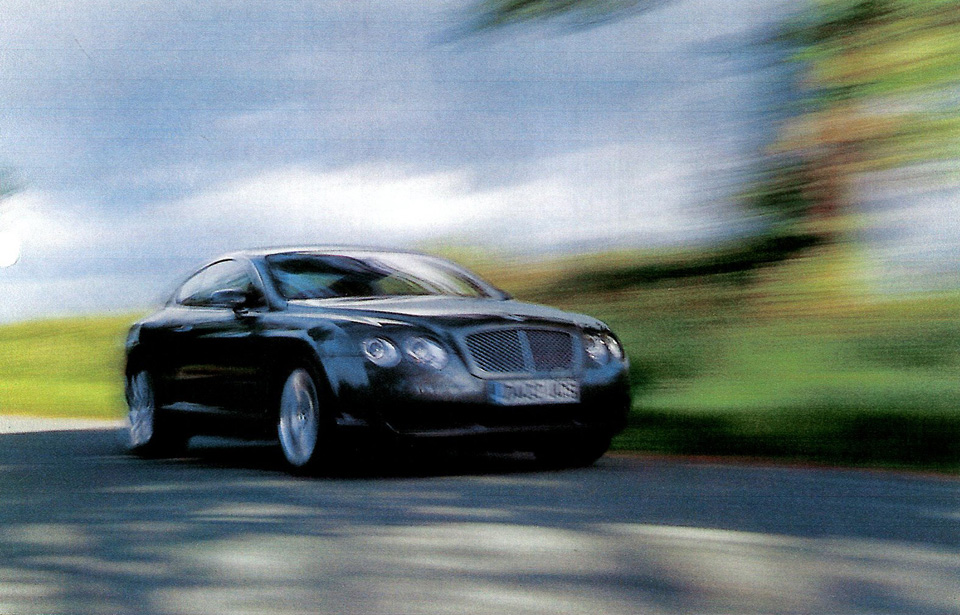

To reinforce this illusion of continuity, Bentley Motors made a huge investment to enter cars in the grueling 24-hour Le Mans race. This year they won first and second place; before that, the last Bentley victory was in 1930. Indeed, the GT has the startling performance of a race car: The six-liter, twin-turbocharged 12-cylinder engine rockets the car to 60 miles per hour in 4.7 seconds. Its exhaust note affects race car burbling and gurgling-a purely aesthetic distraction divorced from actual performance.

The GT looks like a tiger crouching and eschews all the English luxury car cues: no waterfall grille, no chrome (save for the headlights) and a thin band of brushed stainless steel around the windows, The only essentially English elements are the “haunches” — the prominent fender farings above the front and rear wheels that evoke, very precisely, the 1952 Continental R.

“Our philosophy was not to remake the ’50s car,” says van Braeckel. “It’s the closest model everyone can relate to, but the inspiration came from older cars too — the Speed Six, for example.”

Massive alloy wheels further evoke the racing pedigree. “Wheels are terribly important to an automotive designer,” van Braeckel says. “It’s what our work stands on and how we measure proportions.” Raul Pires, Bentley’s head of exterior design, echoes the sentiment: “The bigger the wheel, the more compact the car appears. A small wheel can make a car look like a tall person with very small feet. We design according to the feet.”

Pires, who, along with van Braeckel, came from Volkswagen’s Skoda unit, sketched the GT in approximately one week. It was important to create a dramatic design quickly that would galvanize the members of the VW board to direct their finest engineers to work on the GT project. “We didn’t want a B-pillar, since we wanted to be able to drop all the glass and have clean, open lines,” van Braeckel says. “But the boss defended our design, which meant the board gave us freedom.”

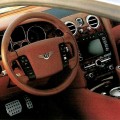

While a sunroof isn’t an option (a convertible will be produced later), a remarkable number of color combinations are available. Because the entire interior is trimmed in leather, there are few plastic surfaces. Also absent are the familiar bits of hardware borrowed from other cars-a Ford window switch here, a Volvo seat switch there, ubiquitous even in super-luxury sports cars like the Aston Martin. Everything one can see or touch is unique to the Bentley; although invisible mechanical parts may be carried over from within the VW group.

The Continental GT cabin is a curious, though luxurious, amalgam of cultures. The traditional Rolls-Royce bull’s-eye vents (with the organ stops to open and close them) and a retro-fancy analog clock dominate the center of the walnut-veneer dashboard. Immediately below is a computer screen, framed by push buttons, for operation of numerous secondary functions, including satellite navigation. Two more horizontal rows of buttons, one styled with a kind of ’50s “aeroplane” theme, lead down to the transmission tunnel. Just behind the leather-wrapped steering wheel are fairly conventional, if deeply recessed, pods containing the speedometer and tachometer.

The $14O,OOO-ish GT is quite literally in a class by itself. The closest competitor might be the Mercedes-Benz CL 55 coupe, as the Aston lvlartin can’t really seat four people.

“A grand tourer should be not only a quick car but one that doesn’t stress the driver,” Dirk van Braeckel remarks. “You can actually get everything into this car — there’s no need to send anything ahead of you or to strap things to the roof. It’s about flexibility.” With all-wheel drive, every possible convenience and acres of style, the Bentley Continental GT is an unpretentious and thrilling entry into the rarefied environment of European sporting life. MG