-

The Dalai Lama

The Dalai LamaAn audience with His Holiness

Interview

For 6 million Tibetan Buddhists, the story of Tenzin Gyatso, Fourteenth Dalai Lama, the supreme temporal and spiritual leader of Tibet, is as important as the rising sun. The journey began with a vision which led a search party to a two-year old peasant boy; on his body were the eight marks that distinguished his thirteen predecessors. At the age of four he assumed leadership of Tibet. Now, forty years later, he lives in exile in Dharamsala, India with seventy thousand of his refugee followers. From his upbringing in the Potala, a palace which contained the tombs of past Dalai Lamas within it’s thousands of chambers, to this treacherous undercover flight from the invading Chinese across the world’s highest mountains, the Dalai Lama remains a revered and essential figure in the changing Buddhist world.

In reference to the ravaging of virgin forests by woodcutters, Chekhov wrote: “All Russia echoes with the sound of the ax.” So in the Tibetan regions, the Chinese ax daily severs the Buddhist way of life, squashes it’s monastic tradition, and obliterates the inner lives of it’s people. Little more than their dependence on the yak remains unaffected. To know that the Dalai Lama is not bitter is to taste the strength of a man whose Mongolian title means “Ocean of Wisdom.” As we talked in a guest house at Harvard on the last stop of an arduous forty-nine day visit and speaking tour, His Holiness was alert and lively. As he hitched up his bi-colored robes of rough cotton and swung a bit of maroon fabric over his shoulder, his small face remained expressive and open. During the conversation his deep voice produced much resonant giggling and laughter at astonishing intervals and pitches.

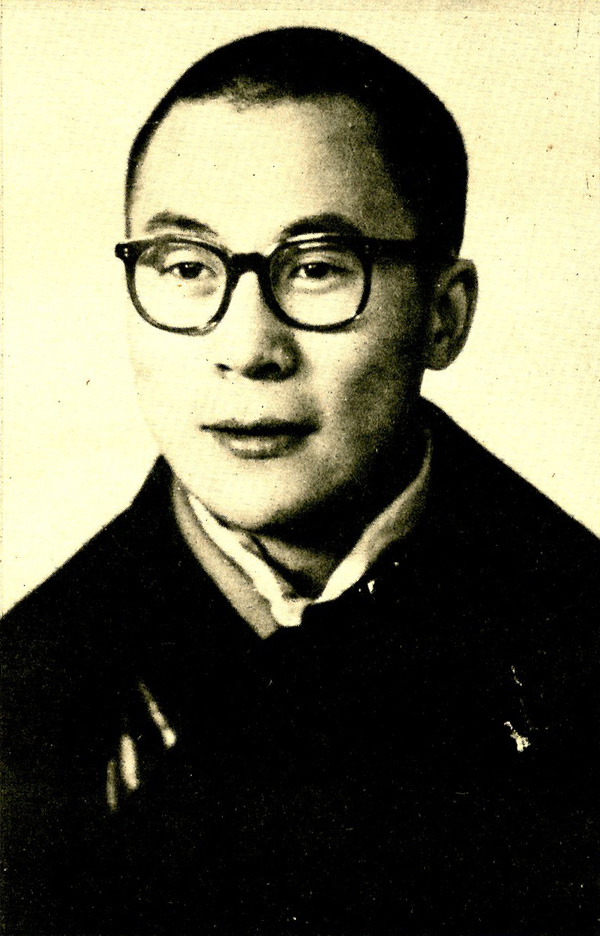

passport photo: His Holiness the Dalai Lama

Mark Ginsburg: Do you ever wish you occupied a more humble position?

HIS HOLINESS: You mean an ordinary role? Yes, as a simple Buddhist monk. That’s the best way to lead one’s life. At the same time you see, in order to help, in order to be of service to certain communities, or human beings in general, my present position is something helpful. So from that viewpoint, it’s okay. Or even better.

MG: Has technology affected our vision of the way we want society to operate?

HH: Definitely, no doubt. Strong effects, strong influence. It circles around the greater concern or involvement with money, and therefore this constant need to rush about and do things.

MG: What is your earliest memory?

HH: A certain moment which occurred when I was two or three years. At some point, some location. I was playing, mainly.

MG: I know you enjoy gadgets and tinkering with electronic devices. Have you ever invented anything?

HH: (laughing) I never invented anything but I’ve always had the urge to try and make something.

MG: What impact do you think you could make on the people of the United, States? Are you playing a role here?

HH: I do not really have a particular role that I want to play or feel I am playing. As a Buddhist monk it Is my duty to explain to those who take interest in Buddhism, a certain Buddhist technique. Beside that I have no particular aim or objective. Generally my purpose is to try to promote a sense of love, kindness, and moral principle. Those people whom I met in the last few weeks generally have a favorable attitude towards my remark. This is all I wish to contribute.

MG: Would this be the same in any country you visit?

HH: Yes! Wherever I go. My real message is one word — kindness, and love. During the last few weeks, wherever I go, I always talk about love and compassion. Some people may be tired of it. (laughing) I’m always teaching compassion; love, and love, and love. It is refreshing, and not complicated but simple, though difficult to practice. We want happiness, not suffering.

MG: But surely the problems in America are different from those in India or other countries where you have spoken.

HH: Certainly there are different problems, but basically I always think of the deeper level. On that level, it’s more or less the same.

MG: What level would that be?

HH: The human level. Beyond different cultures and races. Beyond that, we all are, you see, the same human being. I’m talking on that level. Now we need respect; sincere relations to each other. Helping each otehr and sharing suffering on the basis of love and compassion. It is all the same humanity.

MG: What brings you to the U.S. now, rather than before?

HH: This was not my choice, it’s from the U.S. Government’s attitude. In the past, they were showing a red light; I did not come.

MG: When you were very young, who did you turn to for help with key decisions that changed your life?

HH: I think — collective. I sought advice from several people, as much as possible. Then I’d feel more convinced, irrespective of what name or position that person had.

MG: Now, is it the same?

HH: Yes. But now, of course, I myself have gained more experience. So much easier to make decisions.

MG: Did you find the freedom and democracy here that you had heard so much about abroad?

HH: Very open society, very open. There is a certain amount of freedom, and it seems very good.

MG: How can you get Buddhism to reach a typical American who is wedded to the car and television set without having him think it’s just another cult or religion?

HH: In my mind, without involving any philosophical things or certain beliefs, just act as an honest human being, and lead an honest and good life. That is the real religion, the real Buddhist practice. All religions are on that line. That is the real necessary involvement. Besides that, as a Buddhist, whether we believe in God or rebirth is a different matter. The important thing is daily life, this very life. We must remain honest. Some little contentment is better, but men are always greedy. No time to fulfill all your desire. We must have the facilities but at the same time it is better to have contentment, and more tolerance and patience. You see, we want happiness, it comes from these thoughts. Through greed, competition, anger, hatred, you cannot get real peace, real happiness.

MG: In your Buddhist practice you have meditation. Here we have no systematic means of keeping people honest. Many attitudes, particularly in older people, are fixed. People say, “I’m too old to change,” or “That’s the way I am.” How would you respond to this?

HH: (laughing) All right then. Nothing can be done.

MG: Has the role of the Dalai Lama changed very much through time?

HH: The basic attitude may not change, but there may be differences. For instance, the first four Dalai Lamas remained only religious figures, saintly scholars. The Fifth Dalai Lama also became the head of temporaral power. So it changed. In the future it may change again. But the basic purpose as the important Buddhist head, as the Buddhist son, is helping others and serving as father. That will remain the same.

MG: Regardless of whether it’s called the Dalai Lama or some other name?

HH: You mean my own soul, or self?

MG: Yes.

HH: Hmm. Then you see in the past, I don’t know. As a Buddhist practitioner you believe from low level, from ordinary level, through life practice trying to become better and better and better. So it’s changing. But as I myself practice Bodhisattvayana, sincerely devoted to serving for others, so in future life I will probably remain in that line, and maybe become more … better.

MG: Are you mostly interested in speaking to younger generations?

HH: After all, in the future, the younger generation is the most important. Anyway, younger people will face the problems. Due to good communications, through television and newspaper, different countries have become closer and closer. More open, more liberal attitude towards different cultures, which is positive. The younger generation is more open to this. And they have the main responsibility for the future.

MG: How do you know what is going on in the rest of the world in your exile in Dharamsala?

HH: Through newspaper and the radio broadcast. The BBC, Voice of America, Radio Australia, Radio Moscow, Radio Peking, and so on.

MG: Do you listen to broadcasts often?

HH: Every morning I listen. And I read the magazines, TIME and Newsweek.

MG: Do you compare your role to that of the Pope’s, in any way?

HH: There is not much you can compare! But of course the basic message is the same: peace and love. But then we have different reasons. I, as a Buddhist, just emphasize the human need. In the Christian theory, the reason is God, the wishes of God.

MG: Do you think there is cause for other societies to see the effects of technology on our society as backward in any way? I am suggesting that improvements in technology and high living standard have not led to greater maturity in our people.

HH: It definitely is an advanced society, and historically quite a young nation, from that respect there may be some effects. And also, it is so multi-cultured. Good effects and bad effects,with multi-culture and short history. It seems that here is a society, though I’m not criticizing, with decent facilities and life goes very easy. Sometimes the human standard, and human courage becomes spoiled, the mind becomes soft, and sometimes too superficial. It is worthwhile to think more, and deeper. Everything goes very quickly here, and that affects your mind. You think of some point to investigate, and roughly think, “Yes, this is it,” without sufficiently going deeper.

MG: How do you think the biological and scientific knowledge we have about reproduction and conception has changed our attitudes towards human life? Science seems to give us so many answers to age-old mysteries and wonders.

HH: If you further investigate and talk with doctors, still there is a certain point which could not find an answer. How to perform the physical, that is more or less clear. But besides this physical self, we are experiencting the consciousness of mind. What is the nature of that consciousness, how does it exist? How much relation is there between matter and consciousness? Can consciousness produce by matter, or matter produce by consciousness? These things are yet to solve in science field. So, you see, still there are mysteries.

MG: Are you in contact with Buddhist followers inside Tibet?

HH: Yes, but my contact with Tibetans inside is mainly as a Tibetan, and not on religious matters. I try to carry the movement outside according to the wishes of the Tibetan people. For that I must know what is going on inside, and what are the people’s desires and feelings. I regard myself as a free spokesman for them. The real leaders are inside there, I must get some sort of instruction from them, from their side. So from our information, our report, the situation is not at all satisfactory. The report is confirmed by journalists who have visited Tibet recently.

MG: What kind of help can the Tibetan refugees in India use from Americans?

HH: There are still a few thousand refugees who have yet to settle, but most people in the settlements are quite self-sufficient. In the education and cultural fields we are always spending money, and cannot earn. Here, we talk about culture. Culture is something that belongs to the world in general. Preservation of a particular culture is the responsibility of all human kind. I feel that Tibetan culture is distinctive and unique, though maybe it is presumptuous of me to say it. Also I think it is something useful. So, it is worthwhile to preserve it, and we do so as much as we can. We can use help in this field. We’d be really grateful. We need it.

MG: Can your followers in Tibet practice Buddhism openly now that relations with China have slightly improved?

HH: From the Chinese side, we have a peculiar attitude: on one side they speak of complete freedom of religious practice. At the same time, through newspapers and pamphlets, they have an intense fight about the uselessness of religion and criticize it. They indoctrinate that religion is nothing; on the other hand they say complete religious freedom. But more than ninety-nine percent of the more than 6 million people remain as Tibetans, particularly among the younger generation who don’t want to assimilate into Chinese life, irrespective of whether they are believers or non-believers. They very much like Tibetan dress and Tibetan language. But the ones who know Chinese better have more opportunity and privileged work.

MG: Might you be the last Dalai Lama?

HH: For the Tibetan nation the institution of the Dalai Lama may or may not be convenient, that depends on its value. If the institution is something valuable for our nation, all right, then the next small Dalai Lama may come, as a child. If not, is better to finish.

MG: It has been more than ten years now that you have been waiting to come to the United States. What made you want to come here so badly?

HH: I hold myself as a world citizen. We believe there are many other worlds, I am a citizen of this world, I have a right to visit many places. As a Buddhist monk there is no country in my mind — all people are the same. Each different culture produces a different system and particularly a different religion. I have great respect for the different things and want to see them with my own eyes. And maybe I came just to see the country, although I do not have much time for sightseeing sort of thing. I always talk to people and believe that is more important. To talk and read people’s minds, not just see the outside. It is more useful and much better to get more ideas, and also gives me opportunity to express my own thoughts. That is the only way to build trust and human understanding.

MG: How did the presence of a Chinese enemy, and your subsequent exile, affect your practice and world view?

HH: I gained much more strength through this period. Because of this tragedy, I personally have come closer to reality. I learned tolerance and patience and that is very much helpful to the practice of love and compassion. If I had remained in Lhasa, in Potala, sometimes it was like a golden cage, at some point it was isolation from reality. Now I live in India much closer to the reality and, I think, very grateful to my enemy.

MG: Does Buddhism go through many changes as it is brought to different countries like the United States?

HH: In any religion, there are maybe two aspects: the real essence, religious side, and the cultural heritage. In India, Buddhism arose within Indian culture. Then that Buddhism came to Tibet. The religion is the same, the cultural side may be different, with more Tibetan culture. Now Buddhism in China, in Japan, in Thailand, Mongolia, Siberia, their essence is all the same, the ritual may be different. In America, in Europe, there are some people who practice Buddhism. For them, I feel, there may gradually be an American Buddhism or Western Buddhism, the essence would be the same. The ceremonial things may change from country to country. So it is not worthwhile to try to preserve these things. The social system has influenced the monastic system also. Frankly speaking, once the Lama institution or monastery had land and so forth, then at some point this religious center became almost like a business center. The people, though willing, are mentally business-minded, not religious-minded. So these places must go through changes. It is not necessary to preserve them. Better to let them go. I always emphasize the essence.

MG: What have you learned during your visit to the United States?

HH: My usual belief is that all things are the same, all needs must be met. Material progress alone is not sufficient. This time I learned to be more convinced in this respect. I also learned the explanation according to scientific research about the relationship of consciousness and mind, and about nature of the brain cell, and molecules and atoms. All this sort of thing, which I find interesting. As a Buddhist we are supposed to try to find the fact. Our way is through meditation, inner research. The scientific method is through external instruments. But the point at which to search, I believe, is the same. If it is really proved by scientific means that a thing does not exist, then, even though the explanation for its existence may be in our scripture, we must take two interpretations. Because, you see, we must accept the fact. Because of that attitude, I am very much interested in scientific findings. During my visit here I learned something. Also, many people here showed keen interest in Tibetan culture, and great sympathy toward Tibetan people. I am deeply moved.

MG: What is the relationship like between your seventy-five thousand Tibetan followers and the native population in India?

HH: We are very happy and we’ve settled quite well. Our relationship with the local Indian population is very good, generally, excellent. We’ve made our own Tibetan village, and live by our agriculture and also some small industry, and handicraft centers. We try to preserve our Tibetan identity and culture which the state government and also the people of India are very much in support of. We are grateful to the people of India. Our relationship is extraordinary, no matter with what political party, whether Congress or Janata.

MG: Have Tibetans traditionally had good feelings about their Indian neighbors?

HH: Yes. For thousands of years, we’ve had very close feelings towards each other. When we were in Tibet, despite a difficult journey we tried to get a pilgrimage in India,despite great heights and different climates. Many Indians saw Tibet as a land of enlightenment, so the relationship is historically very deep, so the feelings are warm.

MG: Will you go back to Tibet in this lifetime?

HH: Yes, I think so. MG